Growing Dread: KC, the Wailers and Me

Jennifer Lopez is on my Toronto TV as I write, singing I’m Into You, accompanied by the rapper Lil Wayne. It’s a traditional reggae bass line with a little bit of the more recent dancehall rhythm on top – a sound some of us in my youthful days called flyers rockers, associated with the likes of Johnny Clarke and his None Shall Escape.

The influence of Jamaican “music of the ghetto” on world music culture is as good a point as any to recall episodes of life to mark the 30 years since news broke that Bob Marley had died in a Miami hospital as he sought to get back to Jah Yard as cancer ebbed at his sinews.

The morning remains clear in my mind. As I walked west on North Street alongside the Moravian Church at the Duke Street intersection, headed towards Kingston Public Hospital to visit my grandmother who was a patient there, I met my younger brother Andre headed to school in the opposite direction, having visited grandma.

“Mark you hear? Bob Marley dead!”

“No,” I replied as Andre gave me the summary and continued on to St George’s College. He knew of my association with the Wailers since my school days, my dreadlocked period, my journalistic occupation and what this news meant to me.

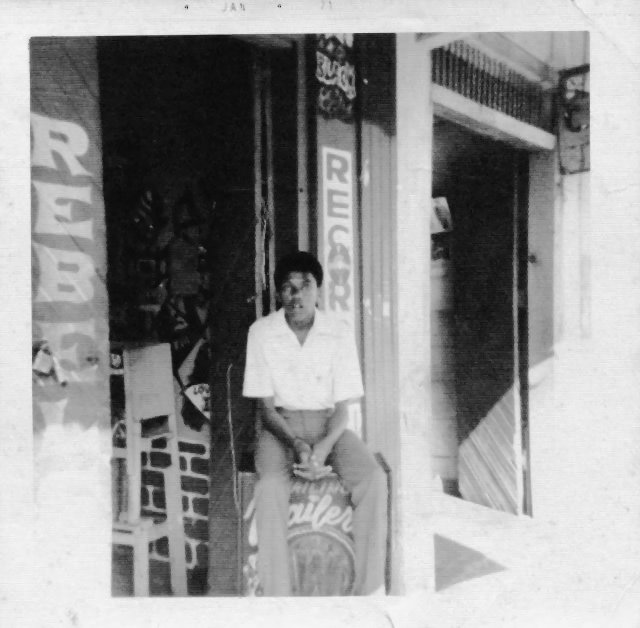

It was on the first day of what was to be my new successful life having got a free place to Kingston College in September 1967, that I bumped into Tyrone Downie. We met flush in the middle of the gate to a footpath on Glenmore Road, that was a shortcut to the campus, asking each other how to get to KC.

We walked in together laughing at ourselves and later in the day discovered that we were in adjoining first form rooms. We weren’t really friends but always spoke when we bumped into each other. KC in 1967 was the high school for boys to attend. In that year, 1967, it probably won every schoolboy team sport event, from Boys’ Athletic Championships, to the Manning Cup football trophy as well as those for basketball, cricket and table tennis.

Not only the poor boys of Kingston who the Rev Percival Gibson had set out to help when in 1925 he established his embryonic ‘university’ – hence the college in the name of the high school – were drawn to the institution, but some of the best minds of Jamaica and the Caribbean found themselves teaching there: in the early 1960s, Erskine Sandiford who would become prime minister of Barbados; Trevor Rhone and Yvonne Jones who would establish Jamaica’s name in theatre and cinematography were our Speech and Drama teachers and Marjorie Whylie our music teacher were just a few of the personalities helping to shape our outlook and displace our ignorance.

Tyrone from first form established his music career, having been drafted first in the world rated Chapel Choir, he mastered the melodica or recorder on the book list for Miss Whylie and then by third form when in the cadets, every instrument he could blow or hit.

My best friend at high school, was my best friend at Rollington Town Primary, Sydney Chang. We knocked about together after school and he invited me while we were at Rollington Town, to join the scout troop at St Aloysius Primary, a catholic school almost in the heart of downtown. After scout meetings, we and the others would hop across Sutton Street to a little shop where we had hot bread and butter or bun and cheese and pop or boxed juices. When we became patrol leaders and had separate meetings for leaders and the general troop, Sydney and I, now in high school, and the others, mainly at St George’s College, upped the after-meeting ante to include punching the juke box in the shop and rocking to the sounds of Roy Shirley, Hopeton Lewis, the Jamaicans and other hit makers of the day.

In Sydney’s form upstairs from mine, was Scoffy, Scof for short, Neil Johnson, who was also eying music as a career. Scoff lived in Greenwich Farm then and he and Siddo became friends so we became a triumvirate, especially when all three of our families moved to the Vineyard Town/Mountain View Avenue area. We chose walking the three or so miles from school in the afternoon making stops along the way at Alpha Academy and Excelsior High to chat up girls under the guise of watching inter-school sports meets.

Scoff and Tyrone had become close, especially after a group of us in third form joined a youth club at the Junior Centre of the Institute of Jamaica, the repository of arts, sciences and culture of the Jamaican establishment.

The Between 12 and Twenty Club (BTTC) changed name to the Junior Centre Action Club, with members drawn from schools around the city: Kingston Technical High, Alpha Academy, Excelsior, Camperdown High, Vauxhall Junior Secondary and some private secondary schools. The members included Tyrone, Desi Jones, who’d go on to be a drummer with Chalice and on the Jamaica jazz scene…

We rehearsed folk music, the staff under Mrs Dorothy Verity devoted much time to us, organizing sessions with institute staff in photography, lecture demonstrations by people like Trinidad master drummer Macky Burnette, young UWI sociologist and folk guitarist Barry Chevannes, and off site classes in steel pan music.

One afternoon in 1968, school was dismissed early and we were urged home because there was rioting in the streets of Kingston. We weren’t quite clear why Black Power students from the University had revolted and at 12 – 13 years old we weren’t aware who Walter Rodney was. But his thoughts were trickling down into the school system. Among young graduates who came to teach in 1969 men were wearing full beards, their hair was not perfectly manicured, women wore Afros and they dressed in African print dashikis and sandals. In fact, during the ’68-’69 academic year, our 2A form mistress and French teacher, Ms Joy Thompson, loaded us on public transport to the ritzy residential Barbican suburb to view the private Inafaca art collection of a middle class medic and Africanist.

Here we were, the first generation of Jamaicans to enter primary school after independence from Britain. The curriculum was just accommodating Sam Selvon, Vic Reid and Andrew Salkey on the junior literature syllabus in the secondary system but only in History was our knowledge of the West Indies formally being tested in the Cambridge General Certificate of Education overseas school leaving exam. Daffodils and tulips, Shakespeare and Chaucer were still the real test of literary interpretation and analysis.

Happily, in our debating society, guided by English master Peter Maxwell, a sometime Jamaica Information Service radio personality, out moots weren’t about empty abstractions but intellectual probe into the issues of the day.

At KC, at both the junior campus at Melbourne Park and the main one a Clovelly Park, North Street, in keeping with its Anglican heritage, chapel remained at the core of school life. St Augustine’s chapel at North Street was a hallowed place for the establishment. You were more likely to be punished with detention for missing chapel during some staff patrol of the form rooms than for any other infraction.

But it was in St Augustine that those of us who braved entering the chapel through one of its huge windows heard Horace Swaby play what was to be his huge hit, Java on the sacrosanct pipe organ. A few times some of us had to make a hasty exit through the windows as the future Augustus Pablo and Organ D belted out a tune and news came that the principal, Dougs (Douglas Forest) was on his way.

By third form, Scoff and I were heavily into monitoring the local hit parade charts of Radio Jamaica and Rediffusion (RJR) the private station and Jamaica Broadcasting Corporation (JBC). We went downtown to Randy’s records at North Parade to collect the charts, not satisfied only to listen to the top ten on the radio, especially with me having the handicap of Seventh Day Adventist grandparents.

Of course we were excited by Nina Simone’s Young Gifted and Black and other US hits of the day but our real excitement was to see how U Roy, Big Youth, Lizzy, Denis Alcapone, Scotty, King Stitt and other DJs were doing. We followed Ken Boothe, Bob Andy and Marcia Griffiths, the Paragons, the Clarendonians, Little Roy, Delroy Wilson, Pat Kelly and the Wailers, instrumentalists Jackie Mittoo, Ansel Collins and Dave Barker. One week, U Roy had the number one, two, four and five hits as Wear You to the Ball woke the town and told the people of reggae’s arrival.

Scoff introduced Tyrone to the Wailers. One afternoon he led Sydney and me to the Wail ’n Soul Tuff Gong record shop at Beeston Street (official address 127 King Street), on the north side two doors east of Chancery Lane. After that we were there almost every afternoon after school and hardly ever went to a Saturday fundraising matinee put on by the International Goodwill Association at the Carib or Regal cinemas in Cross Roads.

Tyrone had made his grand entry to the recording industry playing the organ introduction to Eric Donaldson’s Cherry Oh Baby, a re-release after the first edition was published with a dry drum and bass opening. I was disappointed when Tyrone dropped out of school after third form to join the recording scene.

The shop was run by Johnny Lover, a wanna be DJ, who made his debut with New Kent Road a version of the then ‘it’ rhythm, Old Kent Road. When Lover wasn’t there, Rita Marley was the operator; but as soon as Scoff got there, people would disappear and he would be the shopkeeper, on many occasions until closing time in the late afternoon when he’d lock up and deliver the keys somewhere.

So there we were, selling and buying records, since all the young producers and artists flooded that area which was the Mecca of the business: Just behind the shop was a printing press where 45s and LPs were stamped one at a time by the operators and packaged in boxes of 25 for distribution; around the corner south on Orange Street was Clancy Eccles’ shop, further down on the west side Bunny Lee’s and Sonia Pottinger’s outlets; north, Prince Buster, Coxone’s Studio One and at North Street, Leslie Kong’s Beverley’s. East to King Street, Gregory Isaacs had his African Museum shop on the northwest and on the southeast, Derrick Harriot’s Chariot with his Crystallites label and at Charles Street, Lee Scratch Perry’s Upsetters.

It was here at Beeston Street that we met Ice Water, the reputed writer of the monster hit Johnny Too Bad, who when he went crazy and became a street person rumor had it was because he was robbed by the producers. I can’t verify this anecdote. We met Carrot Top, Harriot’s brother who performed with Scotty in the Crystallites, Keith Hudson and hosts of others.

This was an era of culturing and ferment for the Wailers. Duppy Conqueror and Small Axe established themselves as chart toppers which were not dance music. Earlier they had established their own Wail ’n Soul label with tunes like Thank You Lord and Bus Dem Shut which were underground hits and the Upsetter Lee Perry had set a new standard in Wailers long playing albums with first Soul Rebel and the follow up Soul Revolution Part Two with underground hits like Keep on Moving.

Then there was the collaboration with Johnny Nash, working out of a Russell Heights mansion and work with Leslie Kong’s Beverley’s label. Concurrently, the new Tuff Gong backing band were the Upsetters’ guitarist Alva ‘Reggie’ Lewis, organist Glen Adams and brothers Aston ‘Family Man’ Barrett and Carlton Barrett, on bass guitar and drums respectively.

There was a buzz of excitement as there was talk of a merger with the Wailing Souls whose underground hit Fire Coal Man sounded eerily like the Wailers. There were a string of studio recordings such as one called Harbour Shark that included George, Bread and Pipe of the Wailing Souls (and George was the shopkeeper most on duty).

Rita Marley, Hortense Lewis, sister of Upsetter Alva, and Cecile Campbell, the Soulettes, were laying tacks as well as doing some Wailers harmonies.

One evening Scoff and I were invited to Federal Recording Studio at Bell Road in the city’s west and watched as Trench Town Rock and if I recall correctly, Screw Face (Know Who fi Frighten) and Harbour Shark were laid down. Late that night, about a dozen of us were packed into a two door Ford Escort driven by Bunny, and Scoff and I dropped at Victoria Park just in time to catch the last buses to our homes. Over that period also the original Concrete Jungle track was laid.

(My father was concerned and Rita told me he came to the shop asking questions. When I asked him, he said he wanted to see what had become my distraction and preoccupation instead of school work.)

Rita would arrive with an infant Ziggy; Bunny Wailer’s petite sweetheart, Jean would arrive in an elegant African wrap; Allan Cole the footballer would turn up and so would his dad who walked over from the Government Printing Office and dragged on a cigarette before disappearing; photographer Neville(?) scooted around delivering photo work on his Honda 50 motorcycle and Django, a tall, spooky one eyed character in shades hovered in the background as security. Bob West (Everton McLeary), the Star newspaper’s main entertainment reporter became our friend and would be my colleague later when I would drop out of college to go to work at the Gleaner.

So who were the Wailers? Bob, Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer were like men possessed, continuously on the move on a music mission. They called each other Peter, Bunny and Robbie. Bob came across as the bad boy with the screw face; Peter seemed to be the protector and Bunny seemed to be the philosophical anchor.

One night the shop was broken into and a few items stolen. Scoff heard through the grapevine who had done it, a tall lanky fellow whose name I forget, who frequented the store and the small grocery cum cold supper shop in the same building. One afternoon he was summoned by the trio who leaned against the step wall of a dry cleaners directly opposite the shop.

They told the accused what they had heard and warned him about the consequences of his action. After a good dressing down he broke down and cried. Then glancing towards Scoff and me Peter told him, “An hear me now, nuh mek nutten happen to dem youth ya, you hear me, for dem youth ya a cultured youth.”

Some years later, maybe in 1977, as I worked with the national literacy programme, JAMAL, a team of us went to Kingston’s and Jamaica’s main General Penitentiary at Rae Town for a graduation and media promotional work. “Lee!” I heard someone shout and there with the most brilliant smile was the same guy, who was doing time. And a few years later still, as I walked near the Ministry of Education, he popped up by Campbell Street across the road next to a Chinese grocery, “Lee, mi bredrin, how you do?” he enthused.

By 1971, Big Youth had made flashing dreadlocks on stage an international trade mark, as had U Roy’s locks become an accepted part of the reggae persona. Junior Byles’ Beat Down Babylon and Delroy Wilson’s Better Must Come were anthems against the political regime that had taken the country into independence. Everything Crash by the Ethiopians symbolized the administration.

At school, we were polarized (not divided), not into pro or anti government factions but “soul boys” versus “rebels”. The soul boys had been identified mainly by their neat Afros, black American dress styles and preference for foreign soul music. The rebels were embracing reggae, Africa and then subdivided into political vs religious groups. Some gravitated to the University of the West Indies left wing Workers’ Liberation League, others the Rastafari movement.

We attended African Liberation Day celebrations at centres such as the Marcus Garvey monument at then George VI Memorial Park now National Heroes’ Park. We joined the African Revolutionary Movement (ARM) of lawyer E. K. Brown who changed his name to E. K Banjoko, and attempted to teach Yoruba language and culture.

About then I met Alan Hope who was a schoolmate of a girlfriend’s sister at Kingston Technical High. They hung out at the house in preparation for Merritone sound system party and dance sessions or where percussionist Larry McDonald played. Alan, who was about to graduate, was under the influence of a teacher at KTHS, Marcus Garvey Jr, son of the national hero. While on his search for identity, he started seeing Yvonne, a friend and neighbour of my grandfather’s and he began inviting me to events.

One event to which Alan (now Mutabaruka) invited me was a celebration of the Ethiopian World Federation (EWF) Charter 15, at Davis Lane in Trench Town. Scoff and I went to what would be my first encounter with the Rastafari organization, the 12 Tribes of Israel which was operating under the EWF banner by ‘Dr’ Vernon Carrington, the Prophet Gad to the members, a former pop dancer.

Among the membership were scores of the poor from neighbouring communities but also many of the sons and daughters of Jamaica’s upper and ruling classes. Prominent among the latter were people like Peter Phillips who would become a government minister under a People’s National Party administration and now an opposition member of parliament; Ivan Coore, son of David Coore who was deputy prime minister to Michael Manley after 1972, and Bongo Jerry Small, poet and son of Justice Ronald Hugh Small, a former judge of the Supreme Court. Also among the prominent membership was Daryl Crosskill, a former deputy head boy at KC when I started there, who had by now graduated university.

Rastafari had moved from mere crazy slum religion of weed smokers to serious contender for national ideology. None other than Manley appeared in his landmark campaign for the February 1972 general election with a “rod of correction” allegedly given him by Haile Selassie, the icon of Rastafari, with a campaign reggae sound track. The day after the election as I traveled to school in a ‘Jolly Joseph’ bus, we were delayed by a huge sea of people outside the PNP headquarters on South Camp Road near to the school campus, shouting “Power!” and beating in celebration anything they could lay hold of. Rasta had won Manley the election.

Later that year while a student at the College of Arts, Science and Technology (CAST), I made a second visit to the EWF/12 Tribes with a new friend, Jackson Gordon, an artist who was a tenant of my aunt’s. I joined the organization that had its mission settling those who desired to go to Africa, specifically land at Shashamane, Ethiopia. I wasn’t very active and my membership lapsed until around 1975 when I rejoined.

In the interim the Wailers had released the groundbreaking Catch A Fire album with Island Records and then the more cutting Burnin. I wasn’t in that loop any more and didn’t know what influenced the direction into rock guitars but was elated at the effect and international impact. I knew those guys once. My dad still insisted it was not music. “All they have done is add some American wah-wah but it is not music. Music must have beginning, middle and end. This has no end, they just fade out.”

When the Knatty Dread album landed I was as disappointed as I had been elated at the first two Island releases. There were no Bunny Wailer or Peter Tosh and the harmony was the I-Three of Rita Marley, Marcia Griffiths and Judy Mowatt, reggae’s most dynamic individual women artists. But this was not the Wailers.

Peter came out with his Equal Rights album and Bunny with his philosophical Blackheart Man. It was pleasing to have the triumvirate in their individual glory but for many of us the Wailers had by then passed on.

In 1979, fresh from an attachment in the Eastern Caribbean having successfully completed studies in mass communication at UWI, I was enthused by what I had encountered. True, the radio station in Montserrat to which I had been assigned, had changed its mind when it learned that I wore dreadlocks and I didn’t learn that until I had arrived. The station manager Wilsey White informed me of this under a big tree downtown Plymouth the Sunday afternoon.

But Karney Osborne, my classmate Sonja’s dad, said any friend of his daughter’s was a friend of his and I was welcome to stay in his house as long as I wanted. Two days later he came home for lunch and told me the House of Assembly had met and it was decided that I should report for work. Speaker of the House and UWI resident tutor, Dr Howard Fergus had told the session, that ZJB couldn’t play Peter Tosh and refuse me entry. At the end of my eight-week stay Wilsey was basking in my work as “ours”.

On a trip down to Barbados, I was taken out of the line by immigration police, made to shake out my dreads, count my money to prove I could fund my weekend stay, and call the person I was visiting to verify my bona fides. Finally a sergeant said I could enter. On seeking directions from Seawell airport, theater artist Earl Warner and some brothers en route from CARIFESTA in Cuba eagerly bundled me into a tiny Mini with all their luggage and took me to CBC station where I was to meet my host.

So back in Jamaica, armed with a newspaper I had got from St Lucia (Calling Rastafari I think it was) and elated by the music of Black Stalin and Bro Valentino in Trinidad, I just decided to hop off the bus at Tuff Gong’s spanking new digital studio on Hope Road. Bob, Tyrone, Alvin Patterson the percussionist, Gillie the chef, and others were on the veranda.

“Look dey Tyrone, a who dat?” Bob declared.

“Ah Lee!” Tyrone responded.

“A whey you did dey all dis time?” Bob asked. I explained. School, work, back to school.

“I sight you sometimes at 12 Tribes meeting, outa Hellshire and at…”

“So how you nuh check we?”

“Well, you know how it go, super star an ting, I don’t want to push up…”

“A wha him a deal wid eh Tyrone? Ah wha kind a likkle false pride yuh a deal wid?!”

About then a slim man in jeans with neatly buttoned long sleeved shirt and an apple cap and carrying a brown cardboard suitcase came up.

“I’ve come to see Bob Marley,” he said to the group.

Everyone looked at him amazed because Marley was right there before him.

“Who are you?” somebody asked.

He explained that he had traveled from Paris to see Bob Marley. After a bit of bemusement, someone said “See him there.”

“You Bob Marley?”

“Yeah.”

“You are Bob Marley? You sing, [he sings] ‘I wanna love you and treat you right’?’

“Yeah.”

“Mon Dieu!” He took off his cap and flung it to the floor. “I can die now! I’ve seen Bob Marley! I’ve seen Bob Marley,” and he knelt and kissed the concrete floor.

Later in the morning a game of pick up football is in progress and I join in. “Come inna dis yout, a long time you dey yah!” Marley shouts as he passes me the ball.

I had seen a newsletter printed on card, titled Movement of Jah People. I learn it’s a project under Mrs Booker’s responsibility and one is to be produced per tour and the Babylon By Bus edition is being prepared.

And American woman named Stella Burden is the real actor and somehow I’m willingly co-opted into writing and editing. I show her the newspaper produced by brethren in St Lucia and suggest that newsprint be used rather than the heavy card and she suggests I discuss it with Bob. He agrees and we proceed and the layout is done by Neville Garrick.

While writing a story about the new digital studio, the first in Jamaica, I ask Marley whether I should say something that invites aspiring artists to Tuff Gong.

“Dis is a business!” he says. The publication comes in on time and I get a t-shirt as pay. The music business is not for me.

The last time I see Bob I’m walking in Cross Roads by the roundabout at the end of Tom Redcam Drive as he motors in a VW Bug in the opposite direction. He raises a finger in acknowledgement and I wave back.

I pick up a job at the Jamaica Daily News as a subeditor but leave it after a few weeks. A friend suggests I try for a part time job at CAST’s Commerce Department teaching communication to engineering students. I go in for an interview and am sent around the mulberry bush from department to department but nothing happens. A few weeks later in January 1980, I cut my dreads and return to CAST. After a short chat with the Commerce Department head I’m sent over to the Engineering head and am told to do a course outline and meantime am sent to teach immediately.

The Rasta revolution was an illusion after all. The next year (1981) Marley dies after a battle with cancer. A couple years later I run into Peter at the home of a friend one Sunday afternoon and for some strange reason I was smoking a cigarette. He was upset at the smoke and marched into her bedroom and came back spraying an air freshener and cursing. The “cultured youth” has let him down, I think in my embarrassment.

I was home with my wife one night when the news broke that he had been murdered at his home along with some visitors. Although Bunny Wailer still lives, this is the third death of the Wailers including the dissolution after ‘Burnin’.

Bunny’s music has not made it in the way of Bob’s or Peter’s but it was great for the old school boy to hear Jennifer Lopez May 11, 2011 saying “I’m into you.” There’s no strident message in her reggae but as another KC old boy Dr Leahcim Semaj has suggested, Rasta now is more than the deification of Haile Selassie. It is the recognition of a lifestyle shift in tastes; and the legends live in the music. A dreadlocked barber is on TV right now giving a man a hair cut.

About Mark Lee

Mark Lee has been a long-time journalist writing, editing and producing in print, radio television and new media.

It is important that we write our history, and not only in history books. This informative article records so much of Jamaica’s history and culture to include reggae, Rasta, the educational system, etc., mostly through the eyes of a schoolboy. It makes a nostalgic read. Thanks for the memories, Mark.

Interesting article reminds me of my youth walking on North Stree, going to KC. Neville Garrick the real bob historian

Interesting read!

Great article Mark, those were the days when we had no responsibility but going to school. Remember the gambling casion thet we had established in the music room when we were in third form at north steet.

I remember the evenings when we use to cool ou at the tuff gong record shop after school.

Trouble and the trouble makers as we use to call ourselves during our school days and no one knew who was trouble.

Thanks for the walk down memory lane my best friend and brother Mark.

Great memories, Mark. Of course, one doesn’t have to be a KC man to appreciate and relate to your story. Thanks for sharing this interesting slice of Jamaica’s history.

Fantastic article Mark…Thanks for rekindling those long-lost memories of our KC contempories Tyrone Downie, Sydney Chang & Horace “Augustus Pablo” Swaby, as well as some of our outstanding teachers like Joy Thompson, Marjorie Whylie, Trevor Rhone, Yvonne Jones, Peter Maxwell & Douglas Forrest…I definitely remember our 2A class trip to the Inafca Museum, and also our weekly Africian Revolutionary Movement (ARM) afternoon sessions at EK Bonjoko’s office on Charles Street…these sessions resulted in numerous lifelong friendships among many high school students who came from various economic, social, cultural & political backgrounds.

Good to know that you are alive & well…FORTIS FOREVER.

Ian, great to hear from you and thanks for the reminder of the name of the museum. I’ve moved your comment over to the correct place as comments may have been closed on this article. We must keep in touch.

I have been reminded by Tyrone Downie that it was Scof who introduced him to the Wailers and not the other way round as I had it.

[…] PLEASE CLICK HERE TO CONTINUE READING… […]